Financial markets around the world are increasingly pricing climate risk into investment decisions. Smart money is flowing away from assets that are not compatible with a transition to a net-zero world and toward opportunities that are.

Just as any successful business must be capable of interpreting and reacting to changes in the business environment, countries must also be capable of thoughtful response and action to sustain and enhance their level of prosperity.

As the world moves toward a lower-carbon economy, a key question on which we must collectively focus is how to build on Canada’s comparative advantages in a manner that will create jobs, economic opportunity and prosperity.

Concurrently, geopolitical dynamics and skyrocketing demand have strained value chains, which are essential to the global energy transition. Canada’s European allies have recently experienced the consequences of dependence upon non-like-minded countries for strategic commodities such as oil and gas, and there is a strong desire to avoid similar vulnerabilities in emerging markets such as critical minerals.

Critical minerals present a generational opportunity for Canada in many areas: exploration, extraction, processing, downstream product manufacturing and recycling. This federal government is committed to seizing this opportunity in a way that benefits every region across the country.

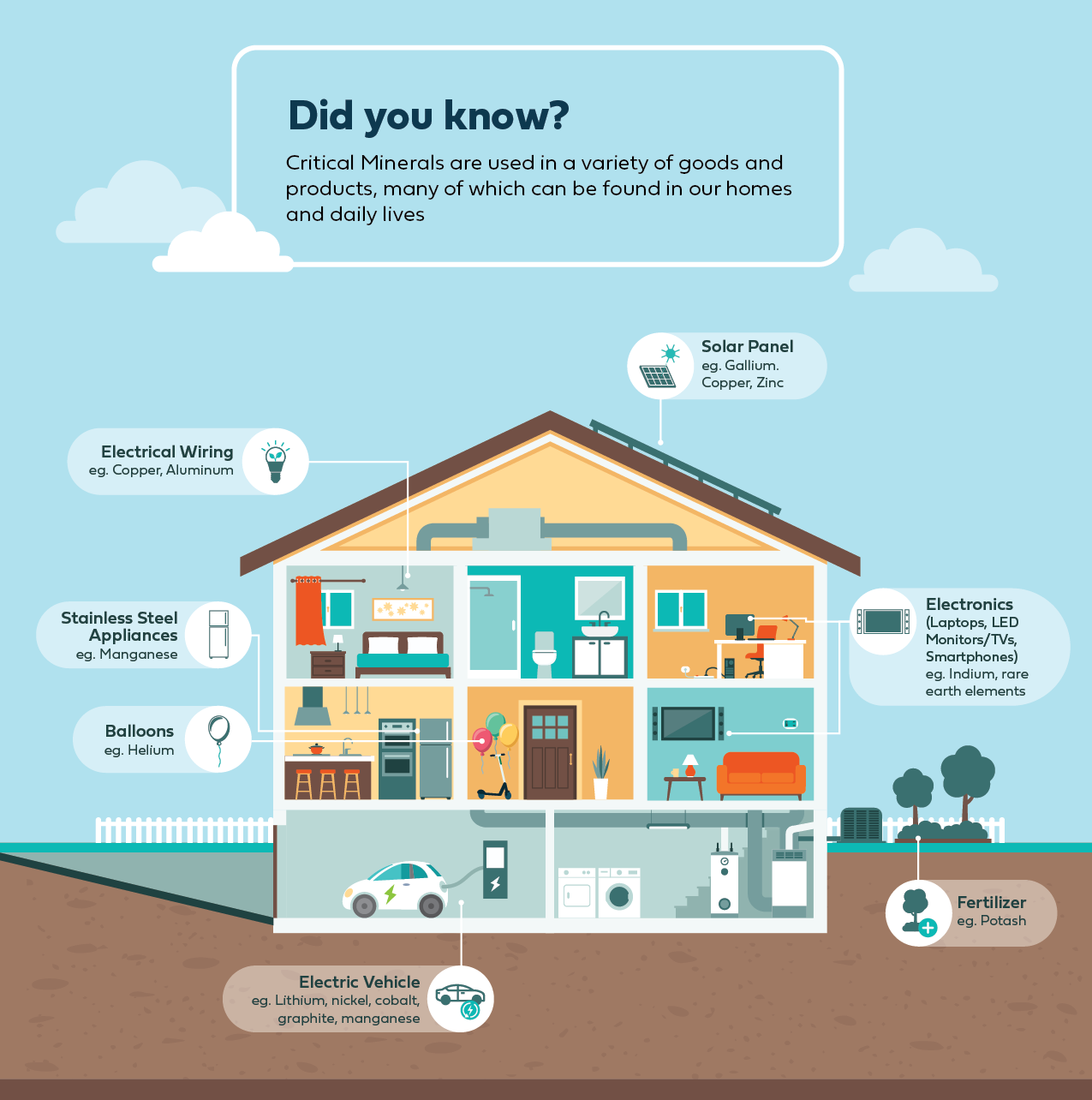

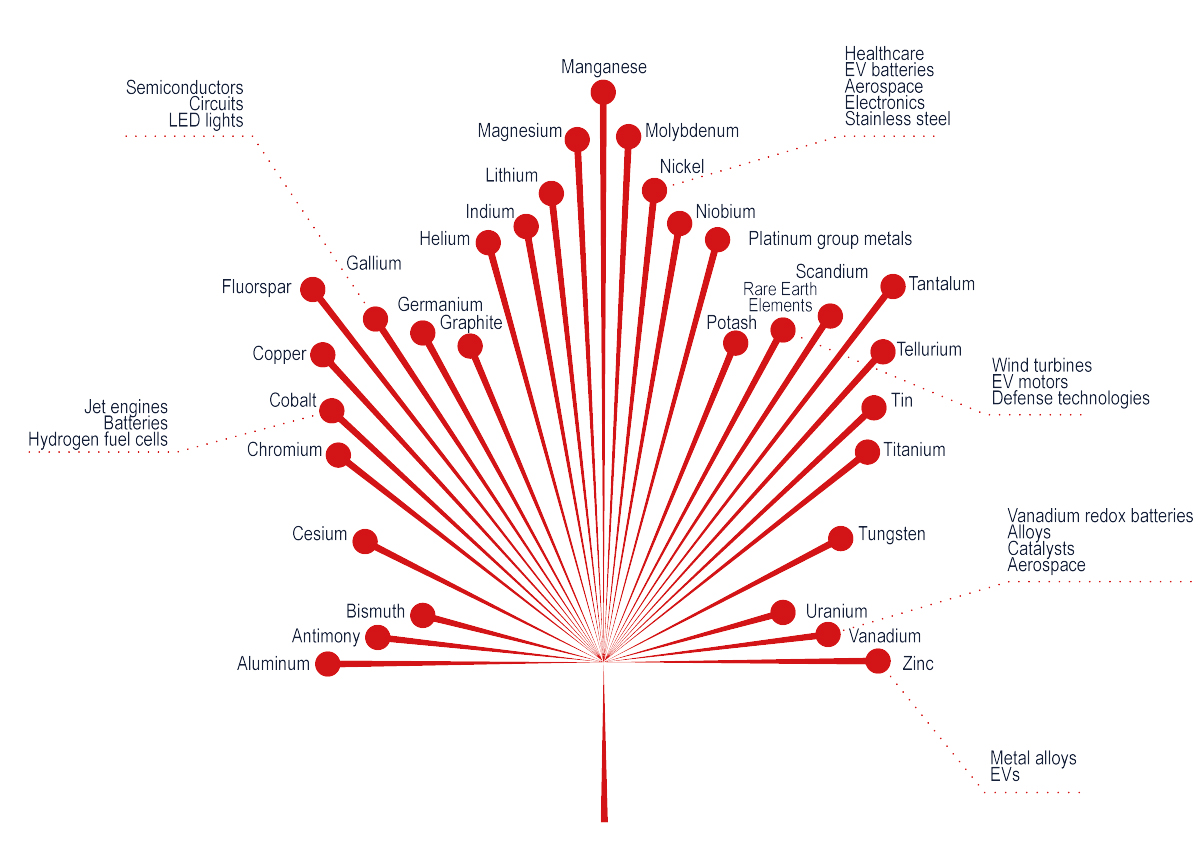

Critical minerals are the building blocks for the green and digital economy. There is no energy transition without critical minerals: no batteries, no electric cars, no wind turbines and no solar panels. The sun provides raw energy, but electricity flows through copper. Wind turbines need manganese, platinum and rare earth magnets. Nuclear power requires uranium. Electric vehicles require batteries made with lithium, cobalt and nickel and magnets. Indium and tellurium are integral to solar panel manufacturing.

It is therefore paramount for countries around the world to establish and maintain resilient critical minerals value chains that adhere to the highest ESG standards. It is also important that we partner with Indigenous peoples — including ensuring that long-term benefits flow to Indigenous communities.

Canada is in the extremely fortunate position of possessing significant amounts of many of the world’s most critical minerals as well as the workers, businesses and communities that know how to scale up our exploration, extraction, processing, manufacturing and recycling of those minerals.

Canada is a world leader in environmental, social and governance standards with respect to mining, with Canadian industry advancing important initiatives such as Towards Sustainable Mining. We are also home to almost half of the world’s publicly listed mining and mineral exploration companies, with a presence in more than 100 countries and a combined market capitalization of $520 billion.

The Government of Canada has worked to build on these advantages in the past several years. We have invested in businesses and workers along the critical minerals value chain, such as the world’s most sustainable potash mine in Saskatchewan, mining of rare earth elements in the Northwest Territories and electric vehicle assembly in Quebec.

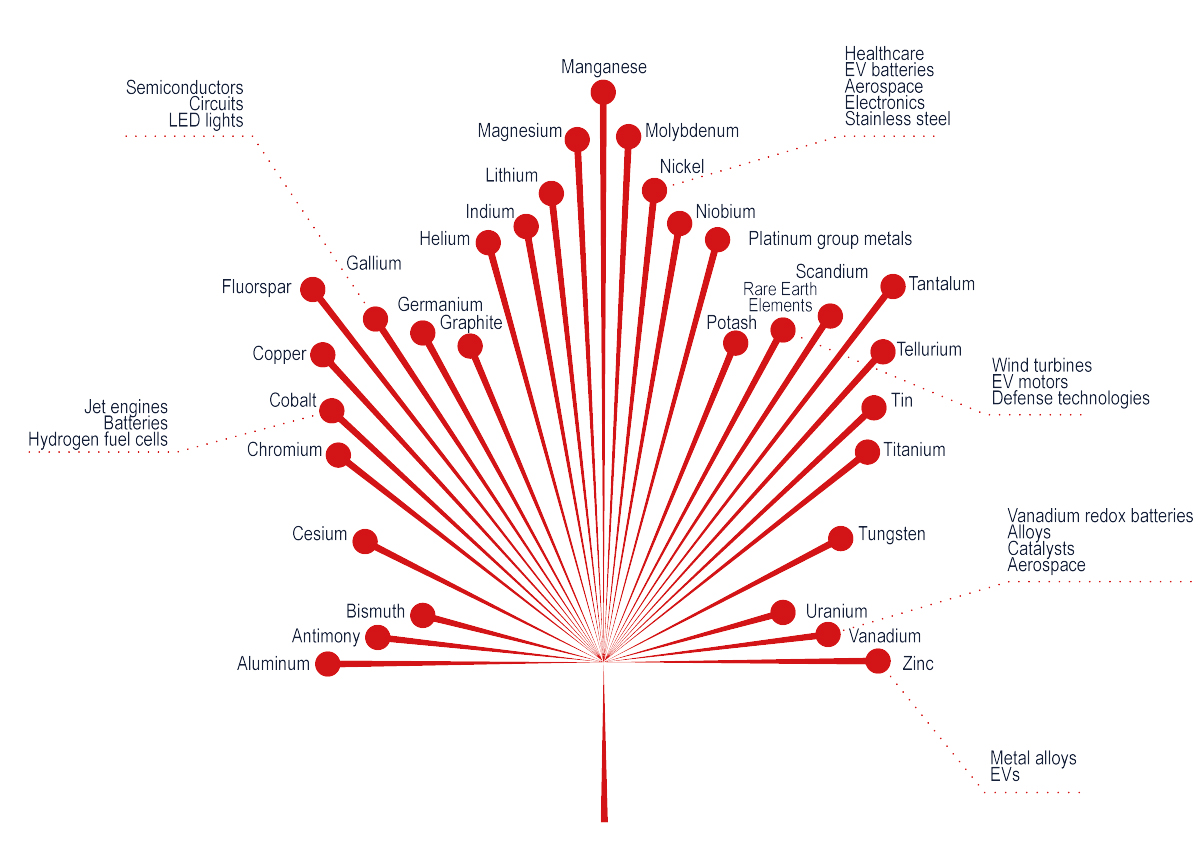

The government has also published the list of 31 minerals that Canada considers “critical” to signal to domestic and international investors where we will focus our efforts, and we have signed cooperation agreements with allies to advance this work together.

Now, I am pleased to release Canada’s Critical Minerals Strategy. This Strategy, backed by nearly $4 billion in Budget 2022, sets out a course for Canada to become a global supplier of choice for critical minerals and the clean digital technologies they enable.

It sets the stage across the country for job creation, economic growth, the advancement of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and close cooperation with Canada’s allies — all in line with Canadian and international climate and nature protection objectives.

The Critical Minerals Strategy is the roadmap to seizing a generational opportunity. A roadmap to creating significant wealth and sustainable jobs in every region of this country. And a roadmap to making Canada a clean energy and technology supplier of choice in a net-zero world.

I look forward to working with Indigenous partners, labour groups, provinces, territories, industry and stakeholders in the implementation of this Strategy in the years to come.

The Honourable Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Natural Resources

The global clean energy transition is under way, and it represents the largest economic transformation since the Industrial Revolution. Canada is poised to seize this generational opportunity—particularly in the critical minerals sector, from mining to refining and from manufacturing to recycling.

Critical minerals are essential to Canada’s strategic industries. They are at the heart of key sectors that drive our economy, including agriculture, manufacturing, artificial intelligence, clean technologies, electric vehicles, energy and much more. They are vital to our everyday lives, and they are essential inputs for the global energy transition, including for wind turbines, electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and semiconductors.

As global demand for critical minerals skyrockets, Canada will be extremely well positioned to take advantage of this opportunity. Thanks to our wealth of critical minerals, our excellence in mining, our skilled labour and our innovation ecosystem, Canada will become the world’s green supplier of choice for critical minerals.

This is particularly true as we continue to strengthen critical minerals supply and promote innovation and sustainable practices across critical minerals value chains. We are doing this in a way that supports regional economic growth; creates a more inclusive and highly skilled workforce; and upholds and strengthens our leading environmental, social and governance standards.

Canada’s leadership in this space has never been more important. The fragility of global supply chains is motivating governments and companies around the world to assess their supply chain resilience for commodities and manufactured goods. It is increasingly clear that Canada can—and will—be the solution.

Through the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy, we are putting our vision into action. We will incentivize new connections and linkages across Canada’s upstream and downstream critical minerals value chains, allowing us to build a strong critical minerals ecosystem while supporting leading-edge digital, clean technology and advanced manufacturing sectors. This strategy will help create and support hundreds of thousands of well-paying jobs across the country, and it will cement Canada’s position as a leader in the low-carbon economy. Together, we must be bold, we must be ambitious, and we must seize the moment.

The Honourable François-Philippe Champagne, Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry

The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy will increase the supply of responsibly sourced critical minerals and support the development of domestic and global value chains for the green and digital economy.

Critical minerals represent a generational opportunity for Canada’s workers, economy, and net-zero future. They are the foundation on which modern technology is built. From solar panels to semiconductors, wind turbines to advanced batteries for storage and transportation, the world needs critical minerals to build these products. Simply put, there is no energy transition without critical minerals, which is why their supply chain resilience has become an increasing priority for advanced economies. By growing Canadian expertise at every point along the critical mineral value chain — from mining to manufacturing, to recycling — we will create good jobs, build a strong, globally competitive Canadian economy, and take real action to fight climate change. As a result of this strategy, we will also better position Canada as a reliable supplier of critical mineral resources to our allies.

The global demand for critical minerals and the manufactured products they go into is required to increase significantly in the coming decades to enable transition to a green and digital economy. Current forecasts show supply deficits if critical mineral production, processing and recycling are not increased. At the same time, the production and processing of many critical minerals are geographically concentrated, making supply vulnerable to economic, geopolitical, environmental, and other risks. With its vast resources and manufacturing capacity, Canada is well positioned to become a secure and reliable supplier of critical minerals and value-added products for global markets.

Growing our supply of critical minerals and the products they go into presents a generational opportunity with domestic and global benefits. To fully seize this opportunity, we must ensure that value is added to the entire supply chain, including exploration, extraction, intermediate processing, advanced manufacturing, and recycling. We must create the necessary conditions for Canadian companies to grow, scale-up, and expand globally in markets that depend on critical minerals. Our efforts must be consistent with Canada’s priorities and objectives including, environmental protection and conservation, safe and responsible labour practices, and respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples.

By growing and building our expertise at each point along the critical mineral supply chain, Canada can grow its economy from coast to coast to coast, fight climate change at home and around the world, and improve the resiliency of our supply chain and those of our allies to future disruptions. Importantly, this must be done in a way that advances the Government of Canada’s commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples through meaningful consultation, early and ongoing engagement, investments in capacity supports, environmental stewardship, community safety, and economic opportunities for Indigenous peoples.

In addition, critical mineral development needs to be sustainable and create nature-forward outcomes with minimal environmental footprint and leading-edge conservation and reclamation practices (i.e., mine closure). A “nature forward” approach to critical minerals development and sourcing means incorporating practices that work to prevent biodiversity loss, protect species at risk, and support nature protection. Innovative ways to capture value from alternative sources and waste streams, recycling technologies, and traditional Indigenous conservation practices are all examples of “nature forward” solutions.

The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy will empower businesses, workers, and communities across Canada to seize this generational opportunity. Accelerating the development of Canada’s critical mineral sector, while ensuring environmental sustainability and respecting the rights of Indigenous peoples, is essential if Canada is to seize upon this generational opportunity and position itself as a stable supplier of critical minerals, both at home and abroad.

Canada’s whole-of-government approach to critical mineral development will be collaborative, forward-looking, iterative, adaptive, and long-term. The initiatives presented in this Strategy will be implemented and refined in collaboration with provincial, territorial, Indigenous, industry, and other Canadian and international partners. They will be updated, as needed, to respond to shifts in domestic and global markets, technologies, and geopolitical considerations. As such, this Strategy will help lay the foundation for Canada’s industrial transformation towards a greener, more secure, and more competitive economy.

The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy addresses five core objectives:

These objectives will be achieved by focusing on six areas of focus:

The success of Canada’s critical mineral development is tied to the active participation of Indigenous peoples, achieved by integrating diverse Indigenous perspectives through ongoing engagement, collaboration, and benefits-sharing. Indigenous peoples are the stewards, right holders and, in some cases, title holders to the land upon which mineral and industrial development takes place. The Government of Canada is renewing relationships with Indigenous peoples through the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDA) , which came into force on June 21, 2021. The Act provides a clear vision for the future to ensure that federal laws reflect the standards set out in the Declaration, while also respecting Aboriginal and Treaty rights recognized and affirmed in the Constitution and seeking to secure free, prior, and informed consent for natural resource projects, including critical mineral development.

The Strategy also emphasizes the conservation and protection of Canada’s natural environment, as well as the promotion of climate action by supporting the transition to a greener economy at home and around the world. Mining and related activities can have significant impacts on communities and ecosystems. Canadians place great value on public health and safety, air and soil quality, and wildlife and habitat preservation. Through this Strategy, Canada will leverage its industrial expertise in environmental, social and governance (ESG) frameworks to develop critical minerals with minimal environmental footprint, in accordance with some of the world’s most responsible regulations. In addition, the Strategy will help advance Canada’s circular economy by aiming to keep resources in circulation, minimizing industrial waste through recycling and other means, and thus contributing to an environmentally responsible and economically competitive critical minerals sector.

The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy complements the vision, principles, and strategic directions of the Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan (CMMP), developed in collaboration with provinces and territories and founded on engagement with industry, Indigenous business representatives, and other stakeholders working to build a stronger, more competitive mining sector.

Canada and other countries have developed defined lists of critical minerals to guide investment and prioritize decision-making to support supply chains. Critical minerals can change with time based on supply and demand, technological development, and shifting societal needs. Some commonly recognized examples of critical minerals include lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite, and zinc, among others. While these country-specific lists differ in their composition internationally, there is a shared view that critical minerals:

There is significant overlap between jurisdictions due to the nature of global supply chains and shared challenges. For example, many critical minerals on Canada’s list are also included on lists by the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Japan. A comparison of Canada’s list relative to those of our partners can be found in Annex E.

Canada has a list of 31 minerals it currently considers to be “critical.” Developed in consultation with provincial, territorial, and industry experts, Canada’s Critical Minerals List provides greater certainty and predictability to investors, developers, communities, and trading partners on national priorities. To be deemed “critical” in Canada, a mineral must be

Canada already produces more than 60 minerals and metals and is a leading global producer of many of the critical minerals on our list, including nickel, potash, aluminum, and uranium. We have the potential to supply even more critical minerals to both domestic and international markets.

Of Canada’s 31 critical minerals, six are initially prioritized in this Strategy for their distinct potential to spur Canadian economic growth and their necessity as inputs for priority supply chains. These six minerals are lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements (Annex B). While these minerals represent the greatest opportunity to fuel domestic manufacturing and will be the initial focus of federal investments, many other minerals present notable prospects for the future. Further, where critical minerals are not used solely for domestic manufacturing, there is value to be captured by increasing exports for allies, and expanding domestic refining, processing and components manufacturing. Examples of these minerals are vanadium, gallium, titanium, scandium, magnesium, tellurium, zinc, niobium, and germanium, along with potash, uranium and aluminum (Annex B). Canada’s list of 31 minerals, as well as the federal government’s priority value chains, will be reviewed and updated every few years.

Critical minerals are the building blocks for the green and digital economy. They are used in a wide range of essential products, from mobile phones to solar panels, electric vehicle batteries to medical and healthcare devices, to military and national defence applications. Without critical minerals, there can be no green energy transition for Canada and the world. By investing in critical minerals today, we are building a sustainable industrial base to support emission-reducing supply chains that will address climate change for generations to come (e.g., net-zero energy and transportation systems).

Growth in green and digital applications is expected to boost the global demand for many critical minerals. According to the International Energy Agency, the energy sector’s overall needs for critical minerals could increase by as much as six times by 2040. The North American zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) market alone is estimated to reach $174 billion by 2030, creating more than 220,000 jobs in mining, processing, and manufacturing.

Based on a report by Clean Energy Canada, a battery supply chain in Canada could directly contribute between $5.7 billion to $24 billion in GDP by 2030 annually, supporting between 18,500 and 81,000 direct jobs, depending on how quickly and ambitiously Canadian governments act. These figures grow to between $15 billion and $59 billion in annual GDP contributions, and 79,000 and 333,000 jobs, when indirect and induced activities and jobs are included. Once realized, these activities would contribute between $2.7 billion and $11 billion annually in combined federal and provincial government revenues.

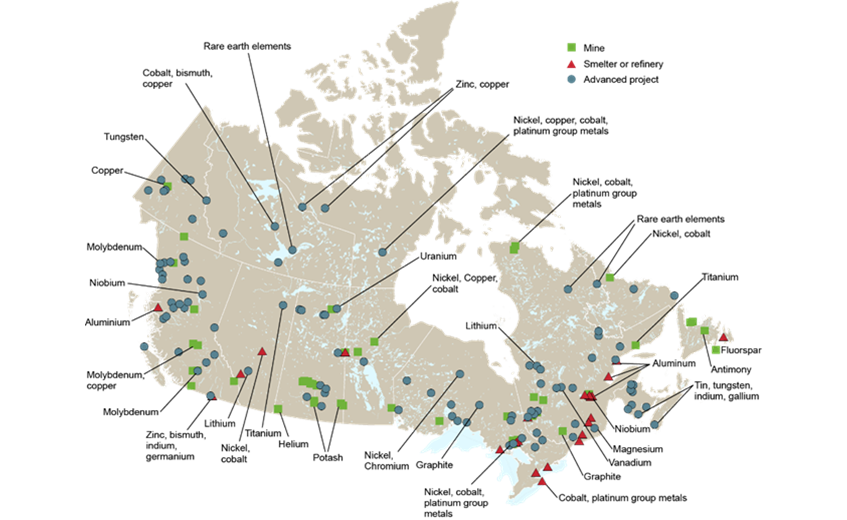

Canada is endowed with enormous resource wealth spread across critical-mineral-rich regions from coast to coast to coast, including rural, remote, and Indigenous communities. For example, Canada is one of the few Western nations that have an abundance of cobalt, graphite, lithium, and nickel — essential to creating the batteries and electric vehicles of the future. Canada is also the world’s second-largest producer of niobium, an important metal for the aerospace industry, and the fourth-largest producer of indium, a key input in semiconductors and many materials needed for advanced vehicle manufacturing.

Our preliminary analysis has identified several Canadian regions with high potential for mineral exploration and development in the near term. Recognizing that these regions are at different stages of development, ongoing analysis and engagement with provinces, territories, Indigenous peoples, and industry experts will be needed to further evaluate their potential and suitability for mineral development, as well as their connection to value chain and consideration of environmental aspects and Indigenous perspectives.

Value chains differ from supply chains. A value chain is the set of activities that add value at each stage of the production and delivery of a product to market (e.g., a product upgrade or process innovation). Value chains tend to improve an industry’s competitive advantage. A supply chain, on the other hand, is a related concept pertaining to the organization and logistics of getting a product to market.

Building on the success of Canada’s Mines to Mobility approach — which has attracted major investments in the manufacturing of zero-emission vehicles — this Strategy focuses on critical mineral exploration to recycling. It goes beyond the foundation established from Mines to Mobility by building capacity at each stage of the value chain, from exploration to recycling, and everything in between.

The value chain for critical minerals includes five segments: geoscience and exploration; mineral extraction; intermediate processing; advanced manufacturing; and, recycling. An illustrative example of a critical mineral value chain is included below.

.png)

At present, the production and processing of many critical minerals are geographically concentrated, making global supply vulnerable to several risks. For example, recent geopolitical events, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, highlight the fragility of critical mineral supply and the need for Canada’s partners and allies to diversify their sources. By ramping up critical mineral production and strengthening their affiliated value chains, Canada and its trusted international partners can reduce their dependency on high-risk imports as demand forecasts outpace mineral supply and investment plans.

To build competitive value chains in Canada, different stages of the industrial process need to be nationally integrated. For example, instead of exporting mineral resources to be processed in foreign countries and reimported as final goods or inputs for domestic manufacturing, Canada can build industrial ecosystems where all stages of the value chain are available and integrated domestically, and with trading partners. Minerals extracted in the Territories could be processed in the Prairies to supply manufacturing operations in other regions of Canada. Industrial suppliers and consumers along the value chain could invest in Canada with greater confidence, in partnership with governments, communities and regional development organizations across the country.

The following value chains have the highest potential for such integration in Canada:

These value chains offer the greatest potential for economic growth and employment across the country. The critical mineral resources needed to build their end products tend to be underdeveloped in Canada, and thus would benefit from government funding to further strengthen the competitiveness of our mining and manufacturing sectors. Developing critical minerals for the green and digital economy is also expected to catalyze foreign direct investment (FDI), helping to create more resilient supply chains. It is in Canada’s advantage to work with allies to pursue increased resiliency in our value chains, which will further enhance our country’s ability to attract investment. Annex B presents more information on the critical minerals implicated in Canada’s high-potential value chains.

As we build new value chains in Canada, we will continue to strengthen and consolidate our existing position as a strong, sustainable producer and global supplier of leading Canadian minerals and metals, like potash, uranium, and aluminum — all critical to the global economy. Whether they represent opportunities in low-carbon energy and electrification, healthcare, green buildings, or food security, we recognize that these minerals are central to Canada’s economic well-being, trading relationships, and strategic global position. Canada’s Trade Commission Services will be a key partner in helping Canadian firms find international business opportunities in these value chains across the world.

Canada has a pipeline of critical mineral projects in advanced stages of development. Canada currently ranks fifth globally in the production of graphite and nickel and is an emerging supplier of many other critical minerals. In 2021, 11% of globally mined nickel and 24% of globally mined graphite were used in batteries. We are also primed to help address the world’s growing demand for lithium.

Canada is the world’s largest producer and exporter of potash, which is primarily used to produce fertilizer. In 2021, Canada accounted for 31% (22.5 million tonnes) of the world’s total potash production and 38% (21.6 million tonnes) of the world’s total potash exports. With the war in Ukraine having created uncertainty about potash supply coming out of eastern Europe, Canadian firms are increasing their production for this essential input for global food security.

This Strategy recognizes Canadian priorities such as human rights, section 35 Aboriginal and treaty rights, climate action, inclusive trade, and the eradication of forced labour. It aims to advance and promote environmental, social, and governance (ESG) priorities across the critical mineral value chain, including support for industry-led approaches such as the Mining Association of Canada’s (MAC) Towards Sustainable Mining initiative, and international standard-setting bodies, such as the International Standards Organization. ESG considerations are becoming increasingly prominent in business and investment decisions. For example, automotive firms have shown heightened interest in ESG frameworks as they transition away from combustion engines towards increased production of electric vehicles. Many mining companies have been implementing their own net-zero objectives, including investments in green technology and process innovations.

As we work to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) of end products and improve responsible business practices, markets, investors, and consumers are increasingly demanding more sustainable practices throughout the value chain. In addition, Canada is seeking to advance efforts that support human rights through collaboration on transparency and traceability in the critical mineral supply chain, as under Canada’s Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA), and through participation in international activities like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. There has also been increased recognition that Indigenous perspectives must be better integrated into ESG standards and ratings to ensure investor certainty while advancing economic reconciliation in Canada’s mining and manufacturing sectors.

The global transition to a greener future is expected to increase the volume of end-of-life clean and digital technologies. For that reason, this Strategy will advance circular solutions to close material loops, increase access to the minerals and metals contained in post-consumer goods through robust recycling infrastructure and secondary markets, and encourage their recovery from mining and industrial waste streams. Circularity will ensure that Canada retains the benefits from the extraction of its critical minerals for decades to come, capitalizing on an industrial segment with untapped potential. As such, it will further cement Canada’s leadership in sustainable industrial practices and ESG frameworks.

Canada’s 2030 Agenda National Strategy, Moving Forward Together , aims to implement the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and highlight Canada’s commitments to promoting and protecting human rights, and leveraging fair and inclusive trade to raise incomes and broaden its benefits for underrepresented groups, such as women and Indigenous peoples. Promoting and encouraging responsible business conduct and proactively addressing risks provides businesses with a stronger social license to operate when facing potential legal, political, and social challenges. Canadian companies active in Indigenous lands are expected to follow established international frameworks and guidelines such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the UN Guiding Principles and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Canada’s expectation for responsible business conduct and due diligence can be found in Canada’s strategy for Responsible Business Conduct Abroad .

The generational opportunity presented by critical minerals is defined by five core objectives, which, if achieved, will indicate that Canada has successfully seized the opportunity before it.

What does success look like?

Recognizing that sustainable critical mineral development is indivisible from our net-zero objectives, Canada wants to advance “nature forward” approaches, which seek to incorporate practices that prevent biodiversity loss, protect species at risk and support nature protection.

While Indigenous leadership and communities across the country will determine how they view success regarding critical mineral development on or near their territories, the Government of Canada will start with the following outcomes:

The Critical Minerals Centre of Excellence (CMCE), housed at Natural Resources Canada, leads the development and coordination of Canada’s policies and programs on critical minerals, in collaboration with federal, provincial, territorial, Indigenous, industry, non-governmental, and international partners. Federal initiatives and investments related to this Strategy will be advanced according to six focus areas: 1) Driving research, innovation, and exploration, 2) Accelerating project development, 3) Building sustainable infrastructure, 4) Advancing reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, 5) Growing a diverse workforce and prosperous communities, and 6) Strengthening global leadership and security.

As a leading mining nation backed by a rich endowment of resources, Canada has vast opportunities when it comes to critical minerals. Exploration is the starting point if we are to make the most of this potential. To unlock these possibilities, we need to expand geoscience and exploration activities to find the deposits of the future, as locating critical minerals in Canada’s vast landmass is a complex endeavour. It requires advanced geoscience capabilities, including geological mapping, geophysical surveying, and scientific assessments and data. The next step is to be able to extract and process critical minerals sustainably. Canada will need to continue developing innovative technologies (e.g., new conversion processes) and industrial practices that optimize efficiency, cost competitiveness, and environmental stewardship.

Budget commitments from 2021 and 2022 cover different aspects of the critical minerals value chain, from exploration to processing and refining, to more advanced products. They include:

The federal government will invest in geological modelling and resource potential mapping for both conventional and unconventional sources, which will help define and enhance our collective knowledge of Canada’s critical minerals landscape. Discoveries of future mineral wealth, particularly in rural, remote, and northern regions, will require advanced technologies at the exploration stage to identify areas of highest potential, while minimizing exploration costs, reducing the carbon footprint of exploration programs, and minimizing the environmental impact on the landscape.

Information and data will be made publicly available to inform development considerations for potential critical mineral projects and to support investment decisions across the supply chain. This includes mobilizing knowledge in a manner that is culturally relevant to Indigenous communities, thus supporting Indigenous evidence-based decision-making. Considered together with other metrics, such as economic and technical feasibility, Indigenous partnerships, and environmental, social, and governance priorities, reliable data at an early stage will help identify exploration opportunities that offer the greatest potential economic benefit and lowest risk to the natural environment.

In addition, Budget 2022 introduced a tax incentive to support exploration for certain critical minerals. The Government of Canada’s proposed Critical Minerals Exploration Tax Credit, in combination with the existing flow-through share program, will provide a significant incentive to investors to support exploration for certain critical minerals in Canada.

To enable the exploration of critical minerals, a new 30 percent Critical Mineral Exploration Tax Credit is being introduced that would be available to investors under certain flow-through shares agreements to support specified exploration expenditures incurred in Canada. This tax credit is applicable to specific critical minerals including nickel, lithium, cobalt, graphite, copper, rare earth elements, vanadium, and uranium, among others.

Finally, the federal government leverages national labs and catalyzes private sector investment to accelerate technological innovation in Canada’s critical minerals sector and associated industries, thus enhancing competitiveness and environmental performance. Building on the momentum of the Critical Minerals Research, Development and Demonstration Program launched in 2021, we will scale up support to de-risk innovations through research, piloting, and deployment to advance sustainable technologies and processes towards commercialization in identified priority value chains. New innovation funding will focus on processing and refining technologies needed to effectively and efficiently transform minerals from primary and secondary sources into intermediate materials, including post-consumer waste (e.g., used batteries) and mining waste (e.g., tailings).

Industry partnerships will be crucial. We will support and directly work with the sector to facilitate the development and deployment of market-ready technologies and innovations (e.g., emerging mining electrification systems, processes to extract value from waste, etc.).

Through a robust network of research and development labs, Canada has the science, technologies, and tools to be a leader in the development of critical minerals. Partnerships with the provinces and territories, Indigenous governments and organizations, academia, and research institutions, as well as industry stakeholders will be key to developing a sustainable pipeline of innovative mineral development projects in Canada. Recognizing potential opportunities in the critical minerals industry, this Strategy provides a targeted commitment to geoscience, exploration, and innovation which is unprecedented in the Canadian mining sector.

To advance our transition to a net-zero economy, the federal government is providing financial and administrative support to accelerate the development of strategic projects in critical mineral mining, processing, manufacturing, and waste reduction (e.g., through recycling and mining value from waste). This support includes strategic investments to unlock potential in critical-mineral-rich regions, leveraging the resources and expertise of federal trade and business development organizations such as the Business Development Bank of Canada, Export Development Canada, and the Canadian Commercial Corporation. It also means capitalizing on existing programs such as the Strategic Innovation Fund (SIF), which is already making significant investments in the electric vehicle battery industries.

Most critical mineral industrial projects require large upfront investments that are higher risk and may generate a slower return. For example, it can presently take anywhere from 5 to 25 years for a mining project to become operational, with no revenue until production starts. Domestic projects are also subject to rigorous federal and provincial/territorial regulatory assessments to meet Canada’s high environmental and social standards.

Budgets 2021 and 2022 include multiple initiatives to help accelerate project development:

The SIF will be one of the most significant direct funding mechanisms in Canada’s toolkit presented under this Strategy. The SIF will help build world-class critical mineral value chains in which prefabrication and manufacturing activities are done domestically by default. It will support projects that decrease or remove reliance on foreign critical mineral inputs across a range of priority industrial sectors or technologies. It will help grow Canada’s critical mineral value chains in areas of research, development, extraction, processing, manufacturing and/or recycling. Finally, SIF investments will favour critical mineral development opportunities that aim to reduce GHG emissions in Canada’s critical mineral and manufacturing sectors.

In 2019, the federal government launched the Mines to Mobility initiative to build a sustainable battery innovation and industrial ecosystem in Canada. To date, the initiative has attracted more than $7 billion in announced investments to capture opportunities in the growing global battery market. It has led to an increased interest in Canada’s value proposition in the battery sector, attracting notable global players in the midstream and upstream segments of our domestic value chain. The federal government will continue to support Canada’s battery ecosystem through the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy by building value chains that position Canada as a global leader in the innovative and sustainable production of ZEV batteries.

text that talks about recent investments into Canada’s battery value chain from domestic and international companies." />

text that talks about recent investments into Canada’s battery value chain from domestic and international companies." />

The Government of Canada recognizes that to meet our ambitious climate and economic objectives to transition to a net-zero economy, additional mechanisms must be in place to expedite and facilitate strategic critical mineral projects from investment and funding opportunities, through regulatory approvals and development, to production. We recognize that, although responsible regulations are vital, complex regulatory and permitting processes can hinder the economic competitiveness of the sector and increase investment risk for proponents. As such, the federal government remains committed to sustainable economic development and environmental protection, which go hand-in-hand, in collaborating with Indigenous peoples, as well as the provinces and territories. We are committed to collaboration on impact assessments, informed participation and decision-making, and high environmental standards for critical mineral projects.

We have heard that better coordination and harmonization is needed across all orders of governments and throughout the impact assessment and regulatory/permitting processes, to avoid duplication, streamline requirements, and ensure early Indigenous consultation and engagement in a manner that respects the parameters of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act . Regulatory certainty is a prerequisite for Canada’s economic competitiveness, which is why the federal government is taking the following actions:

For major development projects where both federal and provincial impact or environmental assessments are required, the Government of Canada is committed to meeting the objective of “one project, one assessment” in its review of projects by working with other jurisdictions to reduce duplication and increase efficiency and certainty in the regulatory process. The federal government also recognizes that efficient, effective, and inclusive northern co-management regulatory regimes are important to advance critical mineral projects in the distinct regulatory environment of northern Canada. The meaningful participation and leadership of Indigenous peoples, including shared and informed decision making, is integral to ensure that projects advance, and that Indigenous rights and titles are upheld.

The CMCE will continue to act as the central coordination hub for critical mineral programs within the federal government, assisting partners and stakeholders in navigating Canada’s regulatory processes to advance project development. Recognizing the wealth of expertise that already exists across the Canadian critical mineral sector, the CMCE will also strive to facilitate regional engagement and connections within the sector and communicate industry information and resources to further stimulate project development.

Canada needs to act swiftly in capturing the generational opportunity presented by the growing global demand for critical minerals to support the green and digital economy. The federal government recognizes that predictable and efficient regulatory regimes are a prerequisite for Canada’s economic competitiveness and is making efforts to streamline project assessments and permits. Budgets 2021 and 2022 proposed multiple initiatives to help accelerate critical mineral project development:

Strategic infrastructure investments are key to translating Canada’s critical mineral potential into reality and securing its position as a leading supplier of minerals and materials to fuel demand for clean energy technologies. Canada’s critical mineral sector has tremendous opportunities that remain underdeveloped. Critical mineral deposits are often located in remote areas with challenging terrain and limited access to enabling infrastructure such as roads or grid connectivity. The cost implications of this infrastructure deficit discourage investment and hinder the socio-economic development of local communities that welcome mineral development. It also increases the risks associated with economic and logistical feasibility, particularly with rising inflationary pressures and challenges in global supply chains.

To address this, Budget 2022 includes a provision of up to $1.5 billion for infrastructure development for critical mineral supply chains, with a focus on priority deposits. The federal government is supporting the development of Canada’s critical minerals sector by investing in sustainable energy and transportation infrastructure to support industrial development, unlock priority mineral deposits, improve supply chain resiliency, and facilitate international trade These investments will support Canadian economic development and trade by addressing gaps in enabling infrastructure to unlock priority mineral deposits. Additionally, investments would complement existing clean energy and transportation programming, including the Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB), Transport Canada’s National Trade Corridors Fund (NTCF) and NRCan’s Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways (SREPs) Program. The Strategy would align with other strategic federal investment mechanisms (e.g., the Strategic Innovation Fund), the potential for multi-user benefits to local communities, the advancement of Canada’s goals related to environmental protection, climate adaptation, and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

The Government of Canada recognizes that off-grid mining operations are heavily dependent on GHG emitting energy sources for power, such as diesel, largely due to the lack of access to energy grids in Canada’s northern and remote regions. Potential strategic investments in green energy infrastructure would improve the environmental performance and sustainability of critical mineral development, by integrating renewable and alternative energy solutions throughout the mineral value chain. These potential investments would drive the industry’s competitiveness by reducing energy costs, while advancing climate action by reducing the carbon footprint of industrial activities in environmentally sensitive regions. They would also support improved quality of life and energy security for primarily Indigenous communities in isolated and remote regions.

In regions with high critical mineral potential, there is a need address gaps in enabling energy infrastructure. Addressing these gaps could be achieved through a range of investments including small-scale green energy projects, leveraging, and expanding existing energy network capacity (e.g., hydroelectricity generation and transmission lines), or by enabling innovative technologies to decarbonize mineral development activities and reduce dependence on fossil fuels (e.g., wind, hydrogen, small modular reactors). Given their lack of grid connectivity, northern and remote mining operations are ideal for the integration of renewable and alternative energy sources to support the electrification of mines, including wind, solar, hydrogen, and energy storage solutions. In addition, some Canadian jurisdictions are looking into the potential of small modular reactor (SMRs) technologies to fill energy supply needs of mine sites and communities, in addition to carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technology to reduce carbon emissions from existing energy systems. Renewable and alternative energy solutions represent a strategic opportunity to advance Canada’s critical mineral resources, while improving environmental performance by cutting GHG emissions.

Finally, Canada’s geography and underdeveloped land-based infrastructure across northern regions create logistical challenges for industrial development and access to domestic and international markets. Transportation infrastructure is a major catalyst for critical mineral development, particularly in northern and remote areas. New infrastructure investments aimed at unlocking new mineral projects in resource-rich regions — including roads, rail, and ports — are needed to help Canada’s mining industry provide the minerals and metals required to reach net zero by 2050, in consultation with Indigenous peoples and local communities. Enhancing Canada’s transportation infrastructure in northern and remote regions represents a strategic opportunity to support broader economic growth objectives, Canada’s Arctic sovereignty and national security, and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

With critical minerals playing an integral role in supporting the global green energy transition, Canadians expect the impacts of development on the environment to be managed responsibly. Development impacts may include increased GHG emissions, loss of biodiversity and impacts to freshwater and sensitive land-based and aquatic ecosystems. One-third of global peatlands are located in Canada, spread over 1.1 million square kilometres or about 12% of Canada’s land area. These wetland ecosystems have been identified as a key nature-based climate solution that act as a natural carbon sink, and maintaining their integrity is essential to meeting national climate targets. Concerns have also been raised over the long-term release of carbon resulting from disturbance of peatlands, and the estimated 20-year timeframe to rehabilitate these wetland ecosystems. The Government of Canada recognizes that there is a need to ensure that development includes measures to mitigate these potential environmental impacts and ensure that Canada’s critical minerals sector is developed sustainably.

The Government of Canada’s efforts to advance critical mineral development will be based on respect for Aboriginal and treaty rights, as well as meaningful engagement, partnership, and collaboration with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples and governments. The development of critical mineral value chains presents a significant opportunity to grow the Indigenous economy through jobs, businesses, services, and ownership opportunities. As Canada seeks to advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, we recognize that this Strategy will need to evolve to address key initiatives, like the implementation of UNDA, and emerging priorities from Indigenous partners.

Indigenous peoples are the stewards, rights holders, and in many cases, title holders to the land upon which mineral resources are located. Historically, Indigenous peoples have not always benefited from natural resource development on their traditional territories, and some developments have caused adverse environmental and social impacts on communities. However, over the past few decades, Indigenous participation in the mining sector has grown significantly and there has been a greater emphasis on advancing development in a socially, economically, and environmentally responsible manner. With the majority of current and future critical mineral projects located on or near Indigenous territories, the Government of Canada is dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples to invest in their leadership in critical mineral value chains and to ensure that they benefit from these projects through meaningful engagement and partnership with industry and governments. It is important that decisions related to critical mineral development not only advance and respect Aboriginal and treaty rights to lands, territories, and resources, but also embody Indigenous land stewardship principles and self-determined priorities of communities.

Indigenous peoples are important partners in Canada’s mining industry. The mining sector is the second-largest private sector employer of Indigenous peoples in Canada and provides skills and employment training, contracting opportunities, job guarantees, and community investments. Many Indigenous-owned businesses are involved in the mining supply and services sector, delivering goods and services to mining companies and generating significant economic benefits for their communities. We have heard from mining stakeholders that industry is committed to building strong, progressive relationships with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples across Canada through early engagement, collaboration, and the development of mutually beneficial partnerships. This commitment is supported by industry efforts to respond to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action 92 for the corporate sector by developing protocols related to engagement and relationship-building with Indigenous communities. It is also supported by the fact that more than 500 agreements between Indigenous communities and industry have been signed since the year 2000.

While the Government of Canada recognizes that critical mineral development in Canada offers an opportunity to build on successful Indigenous-industry partnerships, we know that the sector must continue to evolve and create new pathways to help advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. We have heard serious concerns regarding the social, environmental, and gendered risks of critical mineral development on or near Indigenous communities, the potential impacts and cumulative effects of critical mineral development on Aboriginal and treaty rights, and the health and safety of Indigenous peoples, as well as lands, waters, wildlife, and local food sources Additionally, Indigenous peoples continue to face systemic barriers to their participation and leadership in the sector. Barriers commonly cited include economic, business, and community skills and capacity gaps; a need for more Indigenous-led research and inclusion of traditional knowledge; access to competitive capital for equity participation; and, a need for inclusion in planning, participating, and decision-making throughout the project lifecycle from exploration to reclamation. The Government of Canada will work collaboratively with Indigenous peoples to address these barriers and ensure that benefits are derived from responsible critical mineral development.

Through submissions and discussions with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples on the Critical Minerals Strategy, we heard that additional meaningful engagement is required to ensure that Indigenous peoples’ priorities and concerns with respect to critical mineral value chains in Canada are reflected in the implementation of this Strategy. Canada is at an important juncture for advancing reconciliation, including in the minerals and metals sector, which must be done through ongoing dialogue and impactful, collaborative actions with Indigenous peoples. While this Strategy is a high-level frame for current critical mineral investments and principles, the Government of Canada is committed to developing specific actions in collaboration with Indigenous communities over the course of the Strategy’s implementation under four broad themes:

Indigenous peoples should be able to derive equitable economic benefits throughout the critical mineral value chain — from mineral exploration and extraction to material processing, manufacturing, and recycling. Indigenous leaders across Canada have signalled that there is strong interest in seeking ownership stakes in critical mineral projects and related infrastructure (e.g., renewable energy generation, transmission options, community-focused infrastructure, and roads). However, the high borrowing costs required to obtain financial capital can make equity ownership in critical mineral projects uneconomical for many Indigenous groups.

The Government of Canada will work with Indigenous communities and industry to address these challenges and ensure that Indigenous peoples are active partners throughout the entire value chain of responsible critical mineral development in Canada. The government will continue to honour treaty obligations; uphold the duty to consult, with the aim of securing the free, prior, and informed consent of Indigenous peoples; and, move beyond legal obligations by strengthening Indigenous participation and leadership in the sector. In addition:

Aboriginal and treaty rights are recognized and affirmed in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, and recognition of these inherent rights are also a part of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act , which is being implemented by the Government of Canada. Treaties between the Crown (represented by the Government of Canada and/or the provincial or territorial government) and Indigenous peoples are solemn agreements that set out promises, obligations, and benefits for all parties, and serve to reconcile pre-existing Indigenous sovereignty with assumed Crown sovereignty and to define Aboriginal rights guaranteed by section 35 of the Constitution. Modern treaties (those signed since 1975) often include provisions related to resource development opportunities, such as clarity around ownership of surface and/or sub-surface rights, and participation and decision-making in land and resource management (e.g., land use planning and permitting). Most recently, Canada has affirmed respect for rights and governance arrangements set out in Inuit-Crown treaties in the Inuit Nunangat Policy.

The duty to consult is a constitutional obligation of the Crown rooted in the honour of the Crown and the protection of section 35 rights. When conducting critical mineral exploration and development activities, the potential for adverse impacts to Indigenous and treaty rights must be considered, mitigated, and where appropriate, accommodated. As this Strategy is implemented, the Government of Canada will continue to not only uphold its duty to consult obligations for critical minerals projects but will also seek opportunities to go actively beyond this duty to ensure that Indigenous peoples are active partners in critical mineral development through early, meaningful, and ongoing engagement on projects.

The UNDA came into force on June 21, 2021. The Declaration helps to affirm the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of Indigenous peoples. The implementation of UNDA has the potential to make meaningful and positive change to the ways that Indigenous peoples, communities, and businesses participate in natural resource development, including critical mineral value chains in Canada. The federal government engaged with National Indigenous Organizations, Indigenous communities, Indigenous rights holders, industry, and other relevant stakeholders to help inform the development of a Draft Action Plan, which has a legislated deadline for release in 2023. These efforts will better inform the Government of Canada on what it means to meaningfully partner and engage with Indigenous peoples in natural resource development. Actions under the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy will comply with the Government of Canada’s implementation of UNDA.

The Government of Canada understands the importance of environmental protection and stewardship in Indigenous communities and expects mining activities to include measures to avoid and mitigate negative environmental impacts, where possible, to ensure sustainable mining development. Balancing environmental considerations while protecting Indigenous peoples’ lands, water, wildlife, and resources help advance the UNDA’s commitments by mitigating cumulative effects within traditional territory.

In discussions with Indigenous partners, the Government of Canada has heard serious concerns about community safety with respect to critical mineral development. These concerns are also reflected in the 2019 Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls which includes five Calls for Justice specific to the extractive and development industries. These Calls for Justice highlight the need to ensure safety and equity for Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people. The transition to clean technologies presents an opportunity to ensure Indigenous women and 2SLGBTQQIA+ people are included in decision-making processes related to major natural resource projects going forward, including sustainable critical mineral development projects.

Developing Canada’s critical minerals and associated value chains will create jobs and prosperity for communities across the country, including Indigenous communities. The growth of a highly skilled and more representative workforce in the minerals and metals sector will ensure that Canadians can capitalize on these opportunities. Moreover, as lower-emission industries come online, workers from other extractive sectors, like oil and gas, will be able to use their transferable skills to secure high-quality jobs in critical mineral exploration, extraction, processing, manufacturing, and recycling.

The Mining Industry Human Resources Council forecasts that up to 113,000 new workers will be needed by 2030 to meet new demand and replace those workers anticipated to exit the mining workforce. Skill requirements in the minerals and metals sector will also continue to change as the industry adopts and makes use of emerging technologies, such as AI systems, automation, and robotics, while critical minerals demand creates new opportunities midstream in processing, manufacturing, and recycling.

Jobs in the critical minerals sector exist at each stage of the mineral development cycle, from exploration to mine closure, and along the value chain. They include, but are not limited to, geoscientists, mining engineers, and metallurgists, workers skilled in computer technology, heavy equipment operation, emerging technologies like AI and automation, minerals processing, and automotive assembly. As we build the workforce for the future, it will be vital that Canadians are aware of the diverse opportunities available in the sector.

Diversity and inclusion will be a driving force in the recruitment and retention of a talented workforce, capable of providing the technical and leadership skills necessary to support critical mineral development in Canada. Research indicates that a workforce that reflects the diversity of Canada, especially in leadership roles, is linked to better business results both in terms of profitability and in the creation of long-term value. In addition, critical mineral projects provide an opportunity to increase Indigenous employment and participation in natural resource development, especially in northern, remote, and isolated communities. More than 600 Indigenous communities are located near major minerals and metals projects and over 200 Indigenous businesses supply Canada’s extractive industry.

To fully realize the opportunities available in the critical minerals sector, the federal government is leveraging a wide range of actions and initiatives, including:

Canada is committed to a just transition to a net-zero emissions future and supporting the creation of jobs to achieve it. We want to help workers and communities thrive in the new economy, while fostering a diverse industrial sector that includes Indigenous peoples, women, Black and racialized Canadians, people with disabilities, and members of the 2SLGBTQQIA+ community.

The concentration of critical mineral production in a few countries overseas that use non-market-based practices raises the risk of supply chain disruptions and inflated prices of key minerals and materials for Canada and its allies. The risk inherent to this concentration of production is being accentuated by geopolitical events, which further fuels supply uncertainties. In addition, some jurisdictions have not prioritized high environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards, including in the resource development activities they undertake in other countries. As the global economy moves towards net-zero, advanced manufacturers are seeking to ensure their supply chains are carbon competitive, environmentally sustainable, and respectful of human rights. As a trusted and reliable supplier of responsibly sourced mineral and metal products, Canada is well positioned to be a leader in the responsible, inclusive, and sustainable production of critical minerals and resilient value chains. We have a role to play in powering the green and digital economy, both at home and around the world, in a manner that avoids a race to the bottom for the lowest cost output.

Interest in pursuing collective action on critical minerals to support the global green energy transition is growing within several key multilateral organizations, including the Organisation for Economic cooperation and Development (OECD), the G7/G20, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the World Bank, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF), the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), and the Energy Resource Governance Initiative (ERGI). Enhancing Canada’s participation in these forums will help strengthen the linkage between critical minerals and the energy transition, advance Canada’s commitment to responsible supply chains, and further its role as the global leader in responsible and sustainable mining.

Since January 2020, Canada has formalized bilateral cooperation agreements on critical minerals with the United States, the European Union, and Japan, and is actively engaging with additional allies such as the United Kingdom and the Republic of Korea. Canada needs to deliver on its growing number of bilateral commitments and engagements without compromising its ability to deliver on domestically focused programs and priorities.

This Strategy will work to ensure international engagement activities related to critical minerals align with the Government of Canada’s strategic objectives, including Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. It will address broad geopolitical and industrial priorities for Canada’s international engagements to advance secure critical minerals supply chains, as well as potential risks and regional gaps. This work will align with the Government’s commitment in the 2022 Fall Economic Statement to ensure that Canada remains a first-choice destination for businesses to invest and create jobs in light of investments made by other governments such as the United States, through the Inflation Reduction Act and Infrastructure Bill .

There is growing interest to pursue collective action to secure critical mineral value chains across the globe with allies. To ensure enhanced sustainability practices, we will leverage our international partnerships to improve Responsible Business Conduct, ESG standards, and best practices in critical minerals-related activities, including human rights and reconciliation considerations, as a key objective under the Strategy. This includes enhancing the interoperability of systems and standards, increased recognition of ESG performances, and international collaboration on traceability technologies to prevent products from conflict, child labour, and environmentally poor operations from entering the supply chains.

Additional collective actions under existing and new partnerships can further align policies and regulatory approaches, address technical challenges through joint R&D, facilitate trade and reduce barriers, encourage new investment opportunities in Canada, and reinforce supply chain security and stability. These actions include

Critical minerals are strategic assets that contribute to Canada’s prosperity and national security. They are essential to military and security technology supply chains for national security, as well as other value chains of critical importance to Canada’s economic security and prosperity.

A key challenge is the global reliance on non-market economies for the supply of critical minerals, and for the transformation of minerals and metals through processing and production of downstream value-added products. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need to secure and diversify critical mineral supply chains, given that key operations are located in only a handful of regions globally, leaving them exposed to economic disruptions and predatory actions by non-market economies. Non-market economies are taking increasingly aggressive steps to further cement their control of critical minerals markets and achieve foreign policy goals. Geopolitical events such as war and trade disputes are also increasingly affecting global mineral markets, adding to price volatility and supply uncertainty. Heightened trade barriers and weaker access to markets create bottlenecks along supply chains and result in trade disruptions.

Reliable market-based access to sustainable sources of critical minerals, especially in northern and remote locations, is a strategic and economic security consideration for Canada and its allies. We are working towards securing our supply chains by:

The growing global demand for critical minerals represents a generational opportunity for Canada. Critical minerals are the foundation on which modern technology is built. Simply put, there is no green energy transition without critical minerals, which is why their supply chain resilience is an increasing priority for advanced economies. Every stage of the critical mineral value chain presents an opportunity for Canada, from exploration to recycling and everything in between.

Canada’s approach to critical minerals builds on extensive public and Indigenous consultations, including comments received on the Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy Discussion Paper (from June 14 to September 16, 2022), as well as consultations held for the Canadian Minerals and Metals Plan (CMMP). In addition, evidence and recommendations were considered from a series of engagements and roundtables with industry and Indigenous peoples, as well as recommendations included in the June 2021 report of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources, From Mineral Exploration to Advanced Manufacturing: Developing Value Chains for Critical Minerals in Canada , and the March 2022 report of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry and Technology, The Neo Lithium Acquisition: Canada’s National Security Review Process in Action .

This Strategy is intended to be an evergreen document — forward-looking, iterative, and long-term. Its successful implementation will require a coordinated and multi-pronged approach, in collaboration with multiple partners and stakeholders. The following strategic partnerships and engagement forums will help inform implementation of the Strategy over the long term:

The CMCE will continue to lead Canada’s whole-of-government, multi-stakeholder approach to critical mineral development, including the ongoing development and coordination of policies and initiatives under this Strategy. Ongoing engagement with partners and stakeholders will inform future iterations of this evergreen document.

An Exploration to Recycling approach to critical minerals refers to building capacity at each stage of the value chain, from exploration to recycling, and everything in between. A value chain is the set of activities that add value (e.g., product or process innovation) at each stage of the production and delivery of a quality product to a customer, and that maximize a company’s competitive advantage. A supply chain, which is a related concept, is concerned with the logistics and organizations involved in getting the product to market.

Due to factors like geopolitical risks, ESG, and cost considerations, many companies are increasingly prioritizing vertical integration and having as much of the value chain located in close geographic proximity to their primary operations. An EV manufacturer, for example, will benefit if all stages of battery production occur relatively close to its plant, with transparent and trusted suppliers, operating in a stable economic and political climate.

The value chain for critical minerals includes five segments :

Among the critical minerals essential for priority supply chains, advanced manufacturing, clean technologies, and zero-emission vehicles, six hold the most significant potential for Canadian economic growth. These include:

| Critical Minerals | Value Chains | Major Applications | Examples of Specific Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | Clean technologies and defence and security technologies | Batteries, glassware, ceramics | Rechargeable batteries (phones, computers, cameras, and EVs); hydrogen fuel storage; metal alloys (military ballistic armour; aircraft, bicycle, and train components); specialized glass and ceramics; drying and air conditioning systems. |

| Graphite | Clean technologies | Batteries, fuel cells for EVs | Metal foundry lubricants, vehicle brake linings, metal casting wear, crucibles, rechargeable battery anodes, EV fuel cells, electrical motor components, frictionless materials, pencils. |

| Nickel | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Stainless steel, solar panels, batteries, aerospace, and defence applications | Metal alloys (steel, superalloys, non-ferrous alloys), jet and combustion engine components, rechargeable batteries (phones, computers, EVs), industrial manufacturing machines, construction beams, anti-corrosive pipes, cookware, medical implants, power plant components. |

| Cobalt | Clean technologies | Batteries | Battery electrodes; metal alloys; turbine engine components, automobile airbags; catalysts in the petroleum and chemical industries; drying agents for paints, varnishes, and inks; magnets. |

| Copper | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Electrical and electronics products | Power transmission lines, electrical building wiring, vehicle wiring, telecommunication wiring, electronic components. |

| Rare earth elements | Zero-emission vehicles | Permanent magnets for electricity generators and motors | Flat screens, touch screens, LED lights, permanent magnets, electronic components, EV drive trains, wind turbines, aircraft components, vehicle components, speakers, steel manufacturing, battery anodes, chemical catalysts, glass manufacturing, specialized glass lenses. |

While these minerals represent the greatest opportunity to fuel Canadian domestic manufacturing and will be the focus of most investment, many other minerals also present significant prospects for the future. Where critical minerals are not used solely for domestic manufacturing, there is value to be captured by increasing exports to allies and expanding domestic refining, processing, and components manufacturing over the medium to long term. Examples of these minerals include:

| Critical Minerals | Value Chains | Major Applications | Examples of Specific Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanadium | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Alloys, batteries | Metal alloys (steel), military armour plating, vehicle axles, piston rods and crankshafts, vanadium redox flow batteries, nuclear reactor components, manufacturing of superconducting magnets, pigments for ceramics and glass. |

| Gallium | Information and communications | Semiconductors, optoelectronics | Electronic circuit boards, LED devices, semiconductors, specialized thermometers, barometric sensors, solar panels, blue-ray technology, pharmaceuticals. |

| Titanium | Clean technologies | Aerospace and defence | Colour pigments in paint, plastics, and paper; metal alloys (aluminum, steel, molybdenum); aircraft; spacecraft; missiles and rockets; non-corrosive pipes; ship and submarine hulls; medical implants; sunscreen; specialty Li-ion battery anode materials. |

| Scandium | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Advanced alloys (aerospace & defence), fuel cells | Metal alloys (aluminum); commercial and military aircraft; rockets and vehicle components; high-end sports equipment; specialized light bulbs; solid oxide fuel cells; laser research. |

| Magnesium | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Aluminum alloys | Aluminum alloys (aircraft and automobile components); iron manufacturing; flares and fireworks; lightweight consumer goods (laptops, cameras, power tools); fertilizer; animal feed; pharmaceuticals. |

| Tellurium | Clean technologies | Solar power, thermoelectric devices | Metal alloys (copper and steel), solar cells, semiconductors, CDs/DVDs, vulcanized rubber, chemical catalysts in oil refining. |

| Zinc | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Galvanizing | Rust proofing, manufacturing of automobiles, paints, rubber, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, plastics, inks, soaps, batteries, textiles, electronics, baby creams, sunscreen. |

| Niobium | Clean technologies and advanced manufacturing | Construction, transportation | Metal alloys (steel), jet engines, rockets, construction beams, building girders, oil rigs and pipelines, superconducting magnets, MRI scanners, NMR equipment, eyeglasses, titanium niobium oxide anode materials. |

| Germanium | Information and communications, clean technologies, and advanced manufacturing | Optical fibres, satellites, solar cells | Fibre-optic communication networks, camera and microscope lenses, infrared night vision systems, polymerization catalysts. |

It is also important that Canada maintain its position as a world leader in minerals like potash, uranium, and aluminum. These minerals are important for agriculture, nuclear energy, and diverse manufacturing sectors, respectively.

Provinces and territories also consider critical minerals development as strategic priority. Several jurisdictions have developed critical minerals strategies, while others are in the process of developing policies or are actively promoting this sector. The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy will address national gaps and ensure shared benefits from core and complementary investments.

Canada is seeking to build more resilient global supply chains for critical minerals by working with international partners to align policies, raise global economic, social, and governance (ESG) standards, advance joint research and development, and encourage new investment opportunities, among other priorities.

The Canada-U.S. Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals was announced on January 9, 2020, to advance bilateral interest in securing supply chains for the critical minerals needed in strategic manufacturing sectors, including communication technology, aerospace and defence, and clean technology. The Action Plan is guiding cooperation between officials in areas such as industry engagement, innovation, defence supply chains, improving information sharing on mineral resources and potential, and cooperation in multilateral forums. Canada already supplies many of the minerals deemed critical by the United States. In 2020, bilateral mineral trade was valued at $95.6 billion, with 298 Canadian mining companies and a combined $40 billion in Canadian mining assets south of the border.

The Canada-EU Strategic Partnership on Raw Materials is the primary mechanism for engaging the European Commission and European Union Member States in Canada’s critical mineral and battery value chains. The overarching objective of the partnership is to advance the value, security, and sustainability of trade and investment into the critical minerals and metals needed for the transition to a green and digital economy. Agreed areas of collaboration include the integration of raw material value chains; science, technology, and innovation collaboration; and, collaboration in international forums to advance world-class ESG criteria and standards.

The Canada-Japan Sectoral Working Group on Critical Minerals aims to facilitate commercial engagement between Canadian and Japanese businesses across the critical mineral value chain; strengthen government-to-government information sharing; and, encourage cooperation on international standard-setting for critical minerals. It is part of the Canada-Japan Energy Policy Dialogue, where Japan is working to secure the critical mineral supply chains needed for its industrial base and broader green energy transition.

Through other multilateral engagements, Canada is pursuing collective action on critical minerals to support the global transition to green energy and more resilient supply chains. Notable multilateral organizations and initiatives include the G7/G20, the International Energy Agency (IEA), the World Bank, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF), and the Energy Resource Governance Initiative (ERGI).

| Commodity | Canada (2021) | EU (2020) | South Korea (2020) | USA (2022) | Japan (2019) | Australia (2022) | South Africa (2022) | India (2016) | UK (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | x | x | - | x | - | x | - | - | - |

| Antimony | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | x |

| Arsenic | - | - | x | x | - | - | - | - | - |

| Barium | - | x | x | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| Beryllium | - | x | x | x | x | x | - | x | - |

| Bismuth | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | x |

| Boron | - | x | x | - | x | - | - | - | - |

| Cadmium | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cesium | x | - | x | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| Chromium | x | - | x | x | x | x | x | x | - |

| Cobalt | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | x |

| Coking Coal | - | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| Copper | x | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| Fluorspar | x | x | - | x | x | - | - | - | - |

| Gallium | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | x |

| Germanium | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | x | - |

| Graphite | x | x | - | x | x | x | - | x | x |

| Hafnium | - | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | - |

| Helium | x | - | - | - | - | x | - | - | - |

| Indium | x | x | x | x | x | x | - | - | x |

| Iridium | - | - | - | x | - | - | - | - | - |

| Iron ore | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |

| Lead | - | - | - | - | - | - | x | - | - |